Enjoy this interview conducted by SAVE THE FROGS! Volunteer Journalist Elizabeth Meade.

Introduction

In this interview, I spoke with amphibian biologist Steven Allain, a doctoral candidate at the University of Kent in the United Kingdom. Steven studied amphibians for his undergraduate and Masters degrees and is, since 2018, studying reptiles for his Ph.D. research. We discussed the lack of amphibian conservation awareness in the general public, how we can help amphibians, and the ups and downs of studying slimy creatures of all kinds.

Steven has completed his Ph.D. research and is now Dr. Steven Allain!

Steven Allain in the field

What threats are facing amphibians in the UK right now?

We started the discussion with an overview of some of the amphibian conservation issues Steven works with. “People know a lot about birds and mammals, but there is a lot we still don’t know about amphibians. Those with a limited amount of training can have an impact on conservation. A lot comes down to being in the right place at the right time; seeing something important and disseminating this information can have an impact on a species’ conservation action plan,” he said. A lack of awareness of the threats facing amphibians worldwide is a common obstacle for amphibian advocates.

He mentioned some examples of situations in which those in charge of infrastructure fail to consider the needs of these animals: “A highway in France in the 1980’s led to decrease in the European Treefrogs (Hyla arborea). The females couldn’t hear the males due to the noise of the cars. There are now regulations in place to prevent these things from happening. Modern eco-friendly architecture is based on the needs of birds, insects, and mammals, not reptiles and amphibians. People put ponds in the centre of a complex of buildings, but how are animals supposed to find it when it is far from their habitat?”

Additionally, frogs and toads, in particular, do not capture the public’s imagination, despite being quite fascinating: “Most amphibians are generally dull-colored. They are green or brown, unless they are super toxic or live in a very extreme environment where they have elaborate coloration. There are about 7,500 species of frogs and toads, but the average person could name about five. They live in a diverse range of habitats—deserts, mountains, coastal dune systems. They don’t do so well in cold or saltwater because they lose their ability to regulate temperature and such.”

I also asked Steven about how students can prepare for environmental careers. As a university student, the pressure to make the right decisions to start a successful career is a real issue—it is more than simply being motivated to work with amphibians and reptiles.

Common Toads (Bufo bufo)

What can university students who are interested in a career studying reptiles and amphibians do to prepare (e.g. experience, studying, extra education)?

“It’s important to first identify whether or not your university or institution has any professors or teaching staff that actively pursue research in reptiles and amphibians; approach and see if you can get involved, volunteer to help with their projects, etc. If this isn’t possible, as was the case for myself, pursue extra-curricular activities.”

While that may sound difficult for a niche subject such as amphibian conservation, there are actually quite a few organizations dedicated to the topic. “There’s a network called Amphibian and Reptile Groups (ARGs) organized at county level that undertake reptile and amphibian monitoring, management, etc. They are volunteer-led, only a handful of dedicated people there, and it’s always good to have someone else provide extra hands and eyes. In other places, reach out to charitable organizations, non-profits, NGOs, etc. Get an understanding of how everything works.”

The job search for careers in herpetology can be demanding and competitive: “In order to get a job once you graduate, you need like 10 years’ worth of experience. Try to volunteer where you can. This unfortunately isn’t accessible to everybody due to socioeconomic backgrounds and areas where they live. Hopefully, for a lot of people, there will be opportunities out there to put on their CV.”

Toad making a dangerous road crossing

Have you noticed an increase, decrease, or steady rate of graduates of environmental programs choosing to study reptiles and amphibians?

“A steady rate. The reason I see that is that I’ve been going to scientific conferences here in the UK since 2014. There’s always a large number of students, especially Master’s and Ph.D. students. In my mind there hasn’t been a huge or noticeable increase or decrease in the number of students at those meetings.”

However, Steven does believe that the diversity of herpetology students has increased: “The proportion of those students that are female is increasing, and it’s nice to see that. Like most sciences that have been seen as a route for men, it’s gradually changing so it’s not just dominated by crusty old white men, women are slowly moving into the field as well. It’s a breath of fresh air for a number of reasons. Diversity of students is changing rather than the number.”

Slow down driving on wet nights!

What are some challenges that graduates face when pursuing your career, and how do they deal with them?

While working with amphibians is many frog-lovers’ dream, it’s not an easy career path. “In the UK at least, the biggest issue is lack of diversity of reptiles and amphibians. There are only 13 native species in the UK, so there are not that many jobs based around them. There are a number of organizations out there committed to conservation and protection, which are hiring new staff all of the time,” Steven explained.

Of course, there is also the issue that has impacted the entire job market in recent years. However, that isn’t the biggest challenge prospective herpetologists face. “COVID hasn’t exactly favoured graduate jobs in terms of ecology because you couldn’t do anything, but the biggest obstacle is finding a job. The obstacle then is competition between candidates. There is a steady stream of candidates that far outstrips the number of positions. This is the strongest force leading to graduates having trouble finding a job.”

There are some ways that students can attempt to make their CV stand out: “With the volunteering side of things, being out in the field and gaining some experience; if you’re in the right place at the time you may observe a behaviour or see something that hasn’t been observed before. You can then write up a natural history thing for a journal, put it on your CV, and get a competitive edge.”

Steven acknowledges that there are challenges to this approach as well. “It depends on being in the right place at the right time. Not everyone has time to be running around at night chasing frogs around ponds in spring and summer. People should take that opportunity instead of sitting around and watching Netflix. I run around chasing frogs instead of working on my Ph.D. thesis.” He revealed more about his frog-watching activity: “You need to appreciate them, ask questions about population size, and try to be there when you expect them to be at their peak activity. I don’t plan ahead on when I intend to see frogs or toads. If it’s rained and the air is a certain temp, I look at ponds with boots and a torch.”

I then asked Steven to share some of his expertise on reptiles and amphibians—of which he has plenty. He gladly shared his knowledge on UK frogs for SAVE THE FROGS! His insights are likely to engage both UK frog-lovers who are familiar with these species and those who have never heard of them.

Natterjack Toad (Bufo calamita) on the road

What are some of the most interesting things that are unique to British amphibians and reptiles?

Steven gave us a primer on the origins of UK amphibians: “Unfortunately the UK has no unique species, they’re all shared with continental Europe. It’s likely most, if not all of them, were present during last glacial maximum 15,000 years ago. As northern ice sheets started to melt, Britain separated as an ice sheet from the European continent. They were present from at least that point.”

The UK’s reptiles are interesting as well: “They’re extremely cold tolerant. There are 6 native reptiles, 3 snakes, and 3 lizards. 3 of them–2 lizards and 1 snake–give birth to live young. This is an adaptation for colder temperatures. The ground is too cold for eggs, so females retain eggs, and bask more frequently to incubate them more reliably.” This information is more relevant to Steven’s work with snakes—the topic he’s currently focused on.

One particularly interesting species is the Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae). “The UK has 7 native amphibian species—one of which is undergoing reintroduction, the Pool Frog. While they were initially thought to be a non-native species until the early 2000s because some had been introduced from elsewhere in Europe, a couple in Norfolk were found to be native. They went extinct in the late 1990s. Genetic testing and bioacoustics were done, and the closest population was found in Sweden. Lots of Swedish frogs were brought to UK, being head-started and placed back into ponds to boost population numbers. This relocation activity has been undertaken since 2005, for almost 20 years. They’ve only been able to speak openly about it for the past 7-8 years so people wouldn’t trash their habitats or go take them, and they didn’t want people walking around with dogs and stuff on private site. They’re trying to scale up the project. This is the first case of reintroduction of an amphibian species in Europe. It helps to be an island nation, whereas the rest of Europe is attached to the continent, so if a species goes extinct locally animals from elsewhere can move in. Frogs can’t cope with saltwater and swim over to the UK.”

The UK also has some intriguing reptile species: “The common lizard is a viviparous lizard. One of the UK’s lizard species is ovoviviparous, the other is viviparous. All forms of viviparity exist in the UK. This is important to be aware of as evidence suggests grass snakes may be declining due to lack of suitable egg incubation sites. They tend to rely on rotting vegetation, like many other animals. There are now campaigns to build artificial compost heaps on nature reserves to give snakes somewhere to lay their eggs, as opposed to being left in the wild.

Male Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae) calling

What are one or two British amphibians you find particularly interesting, and why?

“The Great Crested Newt (Triturus cristatus) is the largest species of amphibian in terms of overall length but not in weight. It’s a protected species, and has declined massively since 50s where ponds were filled on farmland to increase food production during the war, but there are plenty if you know where to look. The male produces a huge crest in breeding season to help attract females. The orange and black spotted underbelly advertises that they are toxic. In Victorian times, people would lick them to try to have a psychedelic effect. It made them very ill instead but was still seen as a health benefit. Some lady started this fad after she saw her cat chewing on the newt and frothing at the mouth, thought it looked fun, and decided to try it. Voracious predators will eat other newt species in ponds, particularly larvae since they are twice the size of the other two native newt species. You have to see it to be able to understand its marvel. They look like tiny aquatic dinosaurs with white specks on their flanks. They’re quite awe-inspiring; I studied them as an undergraduate so they mean a lot to me. When you share them with other people, they get inspired as well, because people don’t really see newts except when gardening. They’re quite active, some animals are secretive unless you are willing to go out at night and decode their secretive goings-on.

The Midwife Toad (Alytes obstetricans) was introduced in 1900’s. I’ve worked on them alongside my Ph.D. to keep a connection with amphibians so they know I haven’t cheated on them. They have been in the UK since 1903 and are about 5cm in length tops. The males make high-pitched beeping sounds, and people mistake it for a smoke alarm or car alarm. Males carry eggs on their hind legs for 2-6 weeks depending on climate, then drop eggs in the pond. People have tried to raise the eggs away from male artificially and nobody has succeeded. Their breeding ecology is extremely different to that of native amphibians in the UK. There are populations in France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Western Europe and Portugal. They are not likely to be an invasive species, not like an introduced species from North America or Asia.”

Midwife Toad (Alytes obstetricans) with eggs

Do you think the condition of amphibians in the UK is improving/worsening/staying the same?

“I think it’s more stable than it has been, but declines are still ongoing. A lot more people are aware of what’s going on now, and there are lots of campaigns to raise awareness. Trying to reverse the declines from over the last 60 years, if we ever will, that’s the question. A lot more people are working on solutions and problems these days. Tides are turning but it’s a matter of trying to communicate issues to the public.

In March of 2020 (first lockdown), lots of people spent time in gardens and near ponds, which reconnected some of them with nature and rekindled loves they had as a child. Modern society seems to smash connection with nature from people. The pandemic had people asking questions. Hopefully this spring the ponds will be inhabited by amphibians if they weren’t already. There’s been lots of work done to try to do that by small, specialized organizations as well as large ones such as the RSPB, since amphibians are fundamentally linked to other species. Decline is starting to plateau off.

The population will probably go ahead over next years as more people are aware of issues and engaged in conservation in general. More people working on problems are able to disseminate information and have people act upon it.”

Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae) swimming

What are the greatest threats to amphibians in the UK?

“Habitat loss, lots of ponds were lost in the 1950s when agricultural land was converted to square fields because that’s what allowed farmers to maximize yields with increased mechanization. With housing developments, old green space has now become housing estates. Every time we cut these out or divide them, populations get smaller and smaller and slowly disappear.

Also climate change–at the moment we’re having a very mild winter, things have been quite dry, ponds low for this time of year. Amphibians and reptiles have not had time to hibernate properly, they won’t feed until after they’ve bred (around May), their metabolism won’t start until later, if they eat now it might rot in their stomach and they’ll die of septicaemia. Milder winters are potentially catastrophic, especially for small, isolated populations due to habitat loss.”

Steven also mentioned that there is a divide between people and amphibians.

“People don’t see them as charismatic–if you spend time watching them, you realize a lot of them have their own personalities. African bullfrogs, they headbutt each other to get the right to breed with females in a pond. In actual effect, they are psychologically interesting and great problem-solvers–you can’t use tests used on humans or dogs, but research looks at how dart frogs remember where their babies are in bromeliads, the male has to make a 3D map of the environment over an area of maybe 25 square metres with 15-20 metre-high trees to help the female find the eggs again. They can recognize their own eggs. Some try to lay eggs in another flower before male comes to piggyback them around, the other frog might eat the other eggs or reject them.

You need some form of perspective to judge things by. They’re not cute or fluffy, most of them are dull-colored and people don’t interact with them or see them. Same with snakes, snakes are seen as bad. We need to kidnap everyone, take them into the field, have them see these animals for themselves and hopefully they’ll enjoy them.”

Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae) calling

What are the best ways that people in the UK can help conserve amphibians?

“Dig a garden pond—it doesn’t have to be large, I dug one in 2020, only about 60 by 40 by 30 centimetres deep, not big at all. Amphibians can utilize water sources of any type. Anything bigger than a kitchen sink tends to work well. You can get a diversity of plants.

It’s good to be conscious when mowing the lawn or doing any gardening–don’t do it in springtime or late summer when moving towards breeding ponds or metamorphs are leaving ponds. If grass is longer that’s fine, especially if it’s full of frogs. I would love to see frogs. Manicured lawns are not good—don’t use pesticides or herbicides if you do have a pond; they can leach into it and cause harm to amphibians.”

Backyard garden ponds can be great frog habitat

What are best ways that universities and other large private institutions can help conserve amphibians?

“The easiest thing to do would be to try to include amphibians somewhere in the curriculum along their degree-course pathways in environmental studies. There is not much coverage of them in Zoology. My passion led to filling that gap with extracurricular activity, but if they’re covered in university studies that gives people something to go off of.

At this present time there are a hundred or so universities with an Environmental Sciences degree programme. If each has 100 students per year, you’ll have 10,000 students competing for jobs to study pandas, rhinos, or other charismatic megafauna. With reptiles and amphibians, it’s still there, but less extreme. They could do more reptile and amphibian conservation in order to provide students with a way to find out about it.”

I then asked Steven some more questions about his personal experience with reptiles and amphibians.

Steven Allain in the field

Do you often face misconceptions about what you do, or its significance?

“I used to. When I started my undergraduate we had one of those icebreaker things, and people confused herpetology with herpes. People ask on a regular basis ‘why do you care about frogs?’ When they do, I go to town on them, so hopefully they feel enthused about frogs as well.

For example, all of our antibiotics are failing, there are lots of diseases we don’t have drugs for and there is a whole pharmacopoeia within reptiles, amphibians, scorpions, and creatures like that. Midwife toads create a peptide from their skin.” Steven explained that this substance, called alitocin, has antimicrobial properties and it has now been synthesized in a lab and tried as a cure for diabetes.

“There is the whole aesthetic value, and important function of ecosystem. When trying to convince the average person on the street, make it as selfish as possible so they understand what is going on.”

Natterjack Toad (Bufo calamita)

Have you noticed the growing popularity of frogs and toads in memes, online communities, and popular culture? What do you think of this as a professional?

“I have noticed the increase; that may just be because there’s just more people creating memes, who knows. As a professional, some of them are quite cool; me and my friends often share them with one another. If there’s a meme with one of your favourite animals on them, you’ve got to share it, it’s the law. It’s a good way for new audiences to find out about these species, not all are related to conservation or education; some raise awareness of species, and someone can go away and research more.”

Steven is also glad that memes have improved the image of frogs and toads: “For a long time they’ve been associated with witchcraft but that seems to have shifted slightly to more positive memes. Nice to see that a group of animals you work with is no longer maligned as much as it was. I’m still waiting for the deluge of snake memes to take off.”

SAVE THE FROGS! Art by @badlovedesigns

What’s an amphibian you haven’t studied, but would like to study?

“I would like to study poison dart frogs in South America, because they’re toxic; very colourful; and have complex structures of determining where tadpoles and nests are. Would be great to see that in action; you see them in pet stores, but that’s not the same as in the wild. People ask if I have them as pets—I say no because I’ve re-homed them for people who don’t know how to take care of them. I’d probably cry if I saw them in the wild. They are a species that has captivated people from a young age, I have models of them on my desk.”

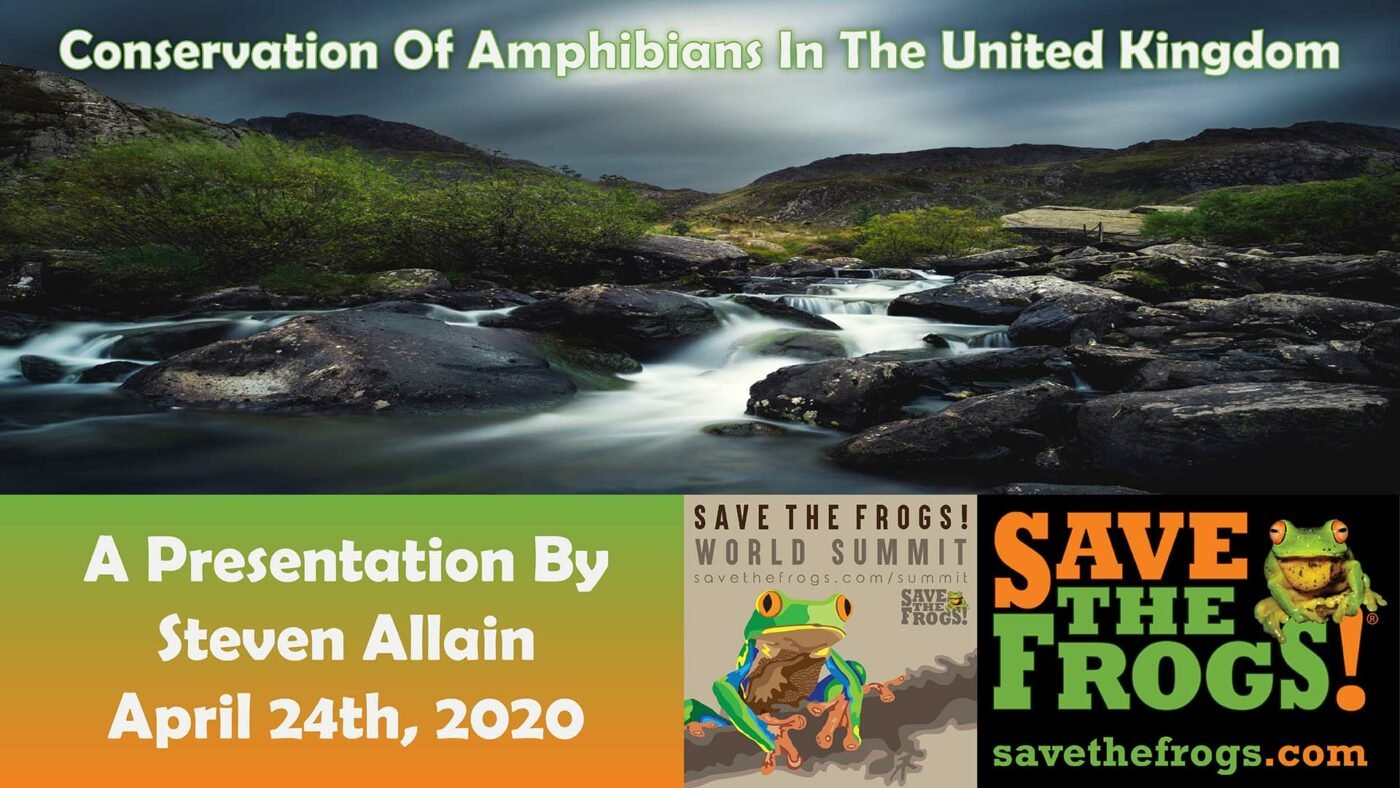

Be sure to watch Steven’s presentation from the 2020 SAVE THE FROGS! World Summit!

I know it is likely hard to choose a favorite amphibian, but is there an amphibian you have particularly enjoyed studying, or that you particularly like?

“I’ve enjoyed studying midwife toads here in the UK the most. We started the project that’s still ongoing; we knew little about them and are slowly filling gaps in. They’re very elusive, hard to find, and make you work hard to get the results you want to get. Ecology is different so you have to put hours in to draw meaningful conclusions; it’s more rewarding in that sense. They’re the cutest little things, make high-pitched beeping sounds, really curious. I can see why they’ve captivated people in the past; they used to be quite a popular pet. If I had to do everything over again, I’d probably still end up studying them, because I enjoy them. My connection with the amphibian world, while I undertake my Ph.D. in reptiles, takes my mind off of the pressure of snake stuff.”

Midwife Toad in its native habitat in Spain, photo by Sara Abad Borraz.

What’s the most memorable experience you’ve had working with British amphibians?

“When I was living in Cambridge undertaking my undergraduate studies, I’d just moved into my new house at the start of second year, and there was a pond about 500-600m away, so I went down there with a couple of friends. It must have been March-April at the time, and we found hundreds of frogs breeding there. I’ve been going to that same pond every year to count the frogs breeding there from 2013, going all the way up to at least 2019: a period of at least 6-7 years. I’m hoping to go back this year. I started looking at a map with friends after having a couple of beers and going ‘let’s go find some frogs!’”

Natterjack Toad posing

What’s it like to work for the British Herpetological Society, and what’s the most interesting/rewarding thing you’ve done with them?

“I’m still working with them; they’re very research-focused, which is great, and they have a number of committees based around conservation, research, captive breeding, and probably another topic. The most rewarding thing I got from that is that we are helping to conserve reptiles and amphibians in the UK indirectly through most of the means, but one of the other ways we are helping them directly is by raising funds for land purchases to conserve their habitats. We haven’t had a committee meeting since before Christmas.

The most rewarding part: being able to donate money to a very good cause to safeguard habitat that would have been turned into a golf course or a housing development since it’s a vital habitat we don’t have the means to lose since we can’t replicate it elsewhere to re-wild that sort of habitat.”

Steven with another amphibian enthusiast at one of his poster displays

Are there any books, shows, or films, fiction or nonfiction, about amphibians that you recommend?

“To those that want to understand more about reptiles and amphibians in the UK and get a sense of what it was like in the 70s and 80s: In Cold Blood by Richard Kerridge. More of a memoir, has a different chapter for each species he would encounter, recalls how he went about finding these species, catching them, admiring them, releasing them or taking them back to his private zoo, didn’t keep any there for too long. People can sympathize with that story of being out in the wild, observing them in their natural habitat. He did this a long time ago, before legislation didn’t allow you to handle protected species. While what he did may be frowned upon now, the way he framed it was very enlightening.

For something more fact-based: A new field guide (2016), Field Guide to Europe’s and Britain’s Reptiles and Amphibians published by Bloomsbury. (If you want to know more about species, it has some wonderful diagrams and beautiful keys, dichotomous keys for species that look similar.) There are also a number of podcasts: Herpetological Highlights and SQUAMATES, which refers to squamate reptiles which is lizards and snakes (some swearing), some hosts get a little too animated and carried away with things. These are helpful, and cover a range of topics. Herpetological Highlights is short and manageable, but SQUAMATES can be up to 3 hours long, if you have a long task you need to do, then stick it on in the background; there are lots of episodes to keep people busy.”

Check out the SAVE THE FROGS! UK webpage!

About The Author

Elizabeth Meade is an MChem candidate and self-proclaimed ‘armchair batrachologist’ who has been advocating for environmental causes since 2008. Her experiences with student journalism inspired her to take the leap to write articles for SAVE THE FROGS!, a group she’s followed since 2010. When she’s not interviewing frog experts, she can be found reviewing speculative fiction, cooking world cuisine, getting involved in politics and gazing at her local pond. You can find out more about her work via LinkedIn and read her other SAVE THE FROGS! articles here.